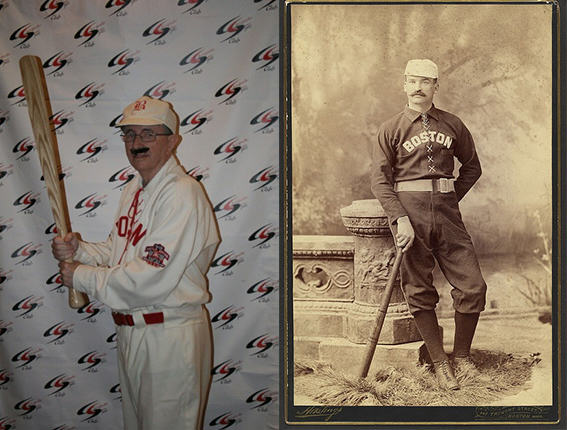

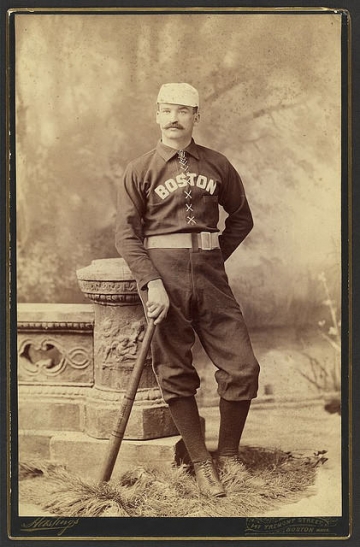

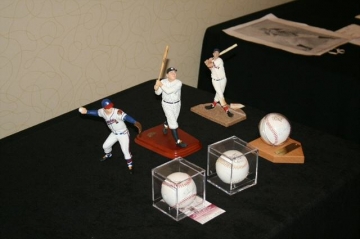

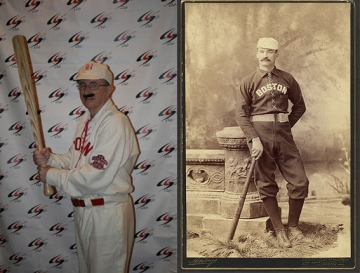

Photos by Chesapeake Sports Club Member Linda Allen Clifton

Our May 13 speaker was Baseball Hall of Famer, Michael Joseph “King” Kelly (aka Eddie Mitchell, baseball historian and Assistant Baseball Coach at Alliance Christian Academy and Nansemond-Suffolk Academy). “King” Kelly talked to the club about his playing days with the Chicago White Stockings and Boston Beaneaters in the late 1800’s. Kelly was one of the most flamboyant and premier players of his day. He was a notorious rule bender on the field and is credited with popularizing various strategies such as the hit and run, the hook slide, and the catcher’s practicer of backing up first base. Kelly was elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945. Various mementos from the early years of baseball was on display. It was an enlightening and entertaining meeting.

Michael Joseph “King” Kelly (December 31, 1857 – November 8, 1894) was an American right fielder, catcher, and manager in various professional American baseball leagues including the National League, International Association, Players’ League, and the American Association. He spent the majority of his 16-season playing career with the Chicago White Stockings and the Boston Beaneaters. Kelly was a player-manager three times in his career – in 1887 for the Beaneaters, in 1890 leading the Boston Reds to the pennant in the only season of the Players’ League’s existence, and in 1891 for the Cincinnati Kelly’s Killers – before his retirement in 1893. He is also often credited with helping to popularize various strategies as a player such as the hit and run, the hook slide, and the catcher’s practice of backing up first base.

In only the second vote since its creation in 1939 the Old Timers Committee elected Kelly to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945.

In concluding where to truly give Kelly credit as an innovator, a 2004 book devoted to 19th-century rule bending in baseball—and which came close to exhaustively accounting for all contemporary reporting on various subjects—placed stress on the following: “Kelly’s hook slide does sound special, and players probably tried to copy it. Also, he seems to have been the first big leaguer to successfully cut a base (when the usually lone umpire wasn’t looking), at least according to the newspaper record.” And, “Kelly could have been the first to foul off lots of pitches on purpose. Doing so was a top trick of some Baltimore players of the 1890s. At the turn of the century, that trick was defused when all foul balls began counting as strikes.”

Kelly’s autobiography Play Ball was published while he was with the Beaneaters in 1888, the first autobiography by a baseball player; it was ghostwritten by Boston baseball writer John J. “Jack” Drohan. Kelly also became a vaudeville performer during his playing career, first performing in Boston where he would recite the now-famous baseball poem “Casey at the Bat,” sometimes butchering it. Kelly’s baserunning innovations are also the subject of the hit 1889 song entitled “Slide, Kelly, Slide” and a 1927 comedy film of the same name.

By 1873, the fifteen-year-old Kelly was good enough to be invited to play baseball on Blondie Purcell’s amateur team in Paterson, which played teams throughout the New York metro area, including the Brooklyn Atlantics from the National Association. From 1875 to 1877, he played three seasons as a semi-pro: in Paterson and then other cities.

In 1877, he was with the Paterson Olympics until around June 10, when he joined the Delawares of Port Jervis, N.Y. In mid-July, a Paterson paper said he had signed with a Springfield, Ohio, team after rejecting a Port Jervis offer of $70 a month. A few weeks later, Port Jervis had not played again when he signed “with the celebrated Buckeye club of Columbus, Ohio.”

He made his big league debut in 1878 with Cincinnati. In 1877, Kelly’s friend Jim McCormick was signed to play for the Columbus Buckeyes of the International Association, and he recommended that his friend Mike be signed to be his catcher. The year after that, Kelly signed to play for the Cincinnati Reds, then known as the Red Stockings. Although the concept would come later, Mike Kelly was now a major leaguer.

After playing in Cincinnati for two years as an outfielder and backup catcher, Cincinnati and Chicago White Stockings players went on a tour of California. While there, Chicago secured him for 1880, then-Chicago Secretary Albert Spalding doing the signing. Later from San Francisco, Kelly wrote Spalding, who was back in Chicago, “Cincinnati Club has gone back on us. Please send expenses. Am broke.” Cincinnati, baseball’s first openly professional team and first powerhouse back in 1869, had fallen on hard times by 1879 and released all their players at the end of that season to save having to pay them a last paycheck.

As of 1879, Chicago was the most important city financially in the National League, as it drew the best attendance for teams taking long train rides from the East Coast.

Kelly was now a young, good-looking man in the big city with money in his pocket. Rather than buying a house, he immediately moved into the Palmer House, the loudest, brashest, most garish and, according to its literature, “fire-proof” hotel in the world.

As a member of the White Stockings, he was annually among the league leaders in most offensive categories, including leading the league in runs from 1884 through 1886 (120, 124 and 155 respectively), and batting in 1884 and 1886 (.354 and .388). One of the best defensive catchers in baseball, he was also one of the first to use a glove and wear a chest protector. Chicago won five pennants while Kelly played for the White Stockings.

After the 1886 season Spalding sold Kelly to the Boston Beaneaters for a then-record $10,000, after Kelly balked at returning to the club. Right before the sale, Chicago writer Happy Palmer quoted Spalding this way, about what he was going to do with Kelly: “Oh, tie him up, I guess, if he really is averse to playing here. He may have his ugly up, and I guess from the way he is holding out in his refusal to sign that that is the case. All right, though. I am willing, and if he keeps on in that spirit I’ll make him eat hay with his horses before he is much older. He has been mad long enough now, and it is pretty near time somebody was getting mad at this end of the line. One thing I can certainly predict and that is that if Mr. Mike Kelly does not sign a contract with Chicago pretty d–d quick, he will have cause to regret it. That is all.”

As a result of the sale, he became known as the “$10,000 Beauty.” In 1881, actress Louise Montague had been so dubbed after winning a $10,000 contest for handsomest woman in the world.

It was in Boston that Mike became “King” Kelly, although he was still overwhelmingly referred to as “Mike” or “The Only” in contemporaneous reporting. As a member of the Beaneaters, he continued to be a key run-producer, scoring 120 runs in 1887 and 1889. He continued to play well and was a great box office draw, but Boston didn’t win any pennants. Freed from the watchful eye of Spalding and Anson, Kelly became less self-disciplined. One day in 1888, Boston player-manager John Morrill fined him $100 for not reporting to the grounds one day. After dinner the night before, Kelly had told Morrill he was ill, and Morrill said he should still report. The Boston Herald said, “Every man on the team thinks [the $100 fine] was deserved.” The Herald also said of Kelly, “At times he goes in and plays with his whole spirit, and he puts life into the team. A sample of that was seen in yesterday’s game, a game that he won for the Bostons. At other times he plays carelessly and indifferently, puts on a spirit of independence, disobeys Morrill on instructions at will, and does as he pleases.”

Kelly managed and played for the Boston Reds in the year-lived Players’ League in 1890, and the Reds won the only Players League title.

During the 1890 season, friends bought him a $10,000 house at South Hingham, Massachusetts, about 15 miles southeast of Boston. Contributors included former umpire John Kelly, the owner of their New York bar; Boston fans Arthur “Hi! Hi!” Dixwell and Frank Norton, and Boston Players’ League President Charles A. Prince and Secretary Julian B. Hart. They gave $300 each, about $6,000 today. Others who gave included John Graham, Jim McCormick, and captains Buck Ewing of New York and John Montgomery “Johnny” Ward of Brooklyn. The house, worth $10,000, could not be mortgaged based on the $1,100 in donations, $400 of which went for a horse and carriage, so in the winter of 1890-91, father-in-law John Headifen “came to the rescue of his (Kelly’s) [sic] friends and subscribed $1800,” the Boston Record said. The Old Colony Savings Bank in Plymouth then gave a matching $2,500 loan, and with that a mortgage was obtained. When he signed with Boston in August 1891, the club’s directors gave him a check for $4,300 for “lifting the mortgage on his ‘popular subscription’ home.”

The house, stable and land would be put up for sale in the spring of 1893 for unpaid taxes of $123, about $2,500 today. It also had a $2,000 mortgage left at five percent interest. In October 1893, the house would be sold.

In 1898, Boston National League Director William H. Conant would recall having paid, around the time of the 1891 payment, a $200 bar bill for Kelly and friends and being forwarded, on a visit to the bar later that night, another Kelly tab for $140.

In 1891, Kelly returned to Cincinnati as the captain of a newly established American Association club there. The team was generally known as the Reds, but were also often called “Kelly’s Killers” in the media due to Kelly’s strong presence. The team was in seventh place when it folded in mid-August, and Kelly signed with the Boston Reds, who had moved to the Association after the Players’ League folded. He spent just four games with the Reds before jumping back across town to the Beaneaters to finish out the season.

After spending the 1892 season with the Beaneaters, batting a career-worst .189, his contract was assigned to the New York Giants for 1893. He played just 20 games for the Giants, batting .269 and driving in 15 runs.

Kelly’s big league career ended after the 1893 season, having compiled 1357 runs, 69 home runs, 950 RBI, and a .308 batting average. Unreliable record-keeping practices of the era prevent an accurate estimate of how many stolen bases Kelly compiled over his career, but statistics kept during his later years indicate he regularly stole 50 or more bases in a season, including a high of 84 in 1887. He also managed to steal six bases in one game.

In 1894, Kelly signed with Albert L. Johnson, the main benefactor of the 1890 Players’ League, to play for his new minor league club in Allentown, Pa. Days before signing him, Johnson had assumed control of the Allentown & Lehigh Valley Traction Company, a trolley line.

In one of the last significant comments about Kelly’s baseball career, financially, while he was still alive, George W. Floyd said the following to the Chicago Herald in March 1894:

“Kelly got the worst of it in every deal he made. When he went from the Boston players’ team [in 1890] to the local [association] club [in 1891] he helped that team to make over $100,000 [about $2 million today]. The club at that time was no better than fifth [not sure if that detail is relevant] and his desertion more than anything else gave the finishing blow to the brotherhood [Players’ League]. Mike was popular wherever he played. The trouble with him was that he had no brain as he himself was concerned. He knew enough to make money for others, but never could make anything for himself. I don’t think that his playing days are over yet, but every club in the league seems inclined to turn him down. Mike has a great many friends in every town where baseball is played and it will be bad policy on the magnates’ [owners’] part to retire him from the game which he has adorned so long.”

In mid-August 1894, Allentown left the Pennsylvania State League for the Eastern League and moved to Yonkers, N.Y., where Johnson also had a streetcar line. “The parting may be cruel and mercenary–but regrets–well, hardly any. So au revoir [goodbye], Mike,” the Allentown City Item said. Before disbanding, Kelly failed to heed Johnson’s instructions to release the players. By not releasing them, his old league was able to file a complaint with baseball’s Board of Control challenging the maneuver. At a meeting in New York, the board ruled that for the next ten days, the Pennsylvania State League could claim Allentown’s players. Eastern League President Pat Powers said Kelly was to blame “and President A. L. Johnson of the latter club [Allentown], who was also present, voiced the same sentiments,” the New York Sun said.

Source: Wikipedia